Moving Beyond the Shock Absorber - Part 9

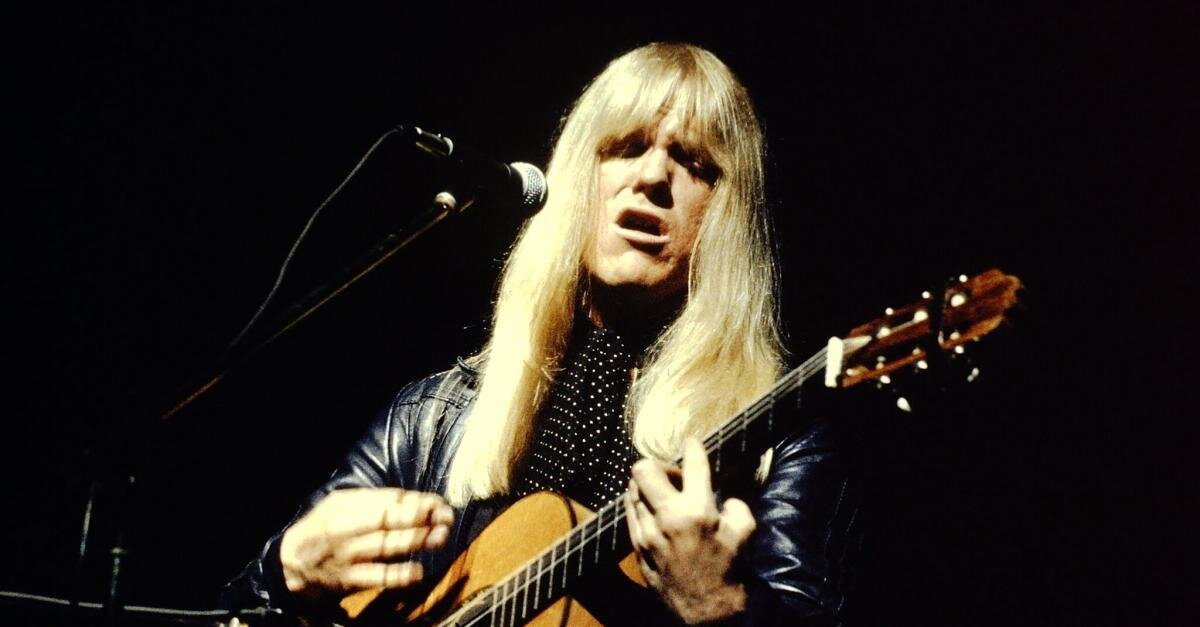

Larry Norman

Part nine of a 10-part series from an article by Stuart Crawshaw that appeared in The Briefing in 2008 titled: Moving beyond the shock absorber: The place of youth ministry—past, present and future

Senter’s cycles accelerate

The Jesus Movement followed the same cycle of youth ministry described by Senter. But while he refers to the Jesus Movement, he does not recognize it as a new cycle in itself. This is because his theory is premised on 50-year cycles. For Senter, the Jesus Movement came in the middle of a cycle started by the Youth For Christ era. But, as already indicated, the Youth for Christ model of ministry was already out of date by the 60s, and was irrelevant to the counterculture of the day.

According to Senter, a new cycle of youth ministry was due during the 90s. However, Senter is too rigid in his expectations: he has not factored in the ever-increasing pace of change brought about by the Industrial Revolution. In other words, as new technologies come online quicker and quicker, change happens more often. Cycles that were once 50 years apart are now coming closer together. Hence, the Jesus Movement occurred only 30 years after the Youth for Christ cycle because the forces that created the counterculture came quickly off the back of the Depression and World War II.

On to institutionalization

The hippie era came to an end, and with it, the Jesus Movement’s relevance. As the rock and roll generation moved on, so did the children of the Jesus Revolution. They were looking for the next step in their Christian expression. As Senter predicted, their success would result in the movement becoming institutionalized. Yet Senter missed the institutionalization of the Jesus Movement, and therefore relegated it to be a subset of the Youth for Christ cycle of youth ministry.

The Jesus Movement did appear to evaporate as the 60s became the 70s. But it also lingered beyond the death of the secular hippie movement. As usual, the process of the shock absorber meant that the Jesus Movement (which had come after the original change in culture) did not pick the end of the movement as it came. Hippie-style music and events continued in some form right into the 80s. But the cutting edge energy of the movement faded as it institutionalized in a surprising way: the unsustainability of the communes became obvious, and when many Jesus People made the necessary journey back into the institutional church, they carried with them their reforms. For instance, they brought aspects of rock ‘n’ roll culture more slowly into the rest of the church, as the shock absorber had always done.

At first, they had responded to the problem of the generation gap by dropping out of the institutional church. But then the Jesus generation created the suburban postmodern church. They were drawn in large numbers to the charismatic movement of the early 70s. Calvary Chapel was one of the early promoters of Jesus rock. Larry Norman, Randy Stonehill, Second Chapter of Acts, Love Song and (arguably the most significant convert to the Jesus Movement) Keith Green all appeared there. Calvary’s leader Chuck Smith saw this youth movement as the work of the Holy Spirit.

Charismatic churches around the world experienced a boom in the 70s and 80s. With less tradition to hold them back, they created a rock ‘n’ roll style, and focused their congregations on a personal relationship with Jesus in an informal setting. It was not as intense an expression as the communes had been, but it had the semiotics of the baby boomer generation.

For those Jesus People in Australia and America who rejoined the mainline churches, there was an added complication: these were the churches that had the tradition and style that the boomers had rejected in the first place. Whereas the mainline adult congregations were inflexible on the place of hymns, the baby boomers were inflexible when it came to rock ‘n’ roll.

A compromise was then reached: many churches maintained a traditional service in the morning, and started a more contemporary youth service in the evening—choir and organ being replaced with guitars, drums and a song leader, just like the coffee house concerts. The two-service structure did not solve the problem of the generation gap, it just accommodated it.

At the time, this made pragmatic sense as it had become widely accepted by baby boomers that their contemporaries would not come to a traditional service. So while preachers may have held conservative views, they redesigned their structures to weaken their community’s expression of that theology. The short-term gains in evangelism effectiveness seemed natural, but the implications for continuity of discipleship of young people was further eroded.

Before this, the Anglican church in Sydney had offered two services on Sunday with the same style: Morning and Evening Prayer allowed all the ages of a local church to gather together at the beginning and the end of the day. This gave young and old proximity to each other. Now old and young were separated from each other. The two generations of the postmodern secular culture had now been structured into the fabric of the local church.

Once this process began, it only grew more divisions within churches. As the 70s turned into the 80s, western culture only became more individualistic and plural. The original generation gap became intergenerational. Change was speeding up so that the distinctions became more complex. Young adults soon saw themselves as very different from teenagers who were only a few years younger. There would also be intra-generation gaps: youth culture multiplied as young people began defining themselves, not only as different from adults, but also different from each other. They developed tribes based on music interests (like pub rock or disco) or sporting activities (like surfing or football).

This meant that the other institutional form of the Jesus Movement in the local church—the Friday night youth group with games, supper and a talk—became quickly outdated. A catch-all group for teenagers was problematic. A rock concert on a Friday night may no longer be relevant to those in the area into disco. The concept of Christian rock had lost its initial curiosity, and so became more uncool than no music at all. The shock absorber was not able to work quickly enough to respond to this plethora of cultures.

The church was changing with postmodern plurality, but not fast enough. When the baby boomers started having children, they found the move to a morning service more practical. However, rather than going to the traditional service, they started a new contemporary family service, which was a morning version of the youth service, complete with rock ‘n’ roll. Now there were three different gatherings in the one church.

This had further implications for discipleship: by the 80s, many teenagers could not look forward to long-term discipleship; as their leaders married and had families and moved to the morning service, they would often hand over their youth leadership responsibilities to a new lot of younger adults.